Vittoria Colonna

(1492–1547)

Born in Marino near Rome into a powerful, aristocratic family, Vittoria Colonna was betrothed at a young age to Francesco Ferrante D’Avalos from Naples, and moved to that city after her marriage in 1509. After her husband was killed following the battle of Pavia in 1525, Colonna spent the rest of her life on the move between the homes of various friends and family members, as well as lodged in the convents where she preferred to live a secluded life. Her fame as a poet grew rapidly after her husband’s death, leading to numerous printed editions of her poems during her lifetime, although none had the author’s official approval.

Described by a contemporary as ‘the first to have begun to write with dignity in verse of spiritual things’, Colonna’s mature poetry moved far from its starting point in the work of Petrarch, to push the lyric genre in new directions. Her spiritually inspired Petrarchan lyrics established a model for later poets, both male and female, and were widely imitated. Her fame in her lifetime was considerable, but after her death Colonna’s poetry suffered the ‘weak history’ of many women writers of the early modern period, and she was largely remembered as Michelangelo’s muse. A recent resurgence of interest in her work has restored her to her rightful place as ‘first lady’ of Italian Renaissance poetry.

Six Sonnets gifted to Michelangelo

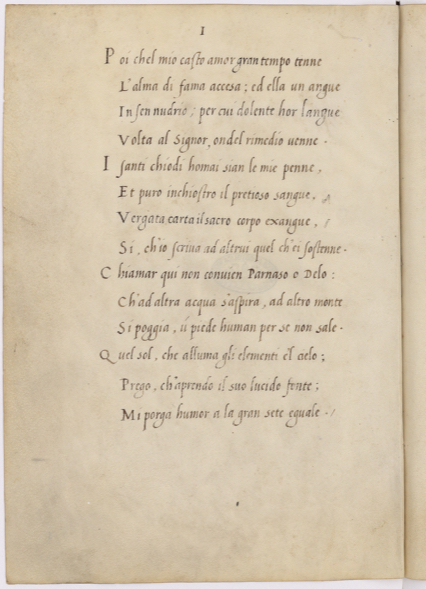

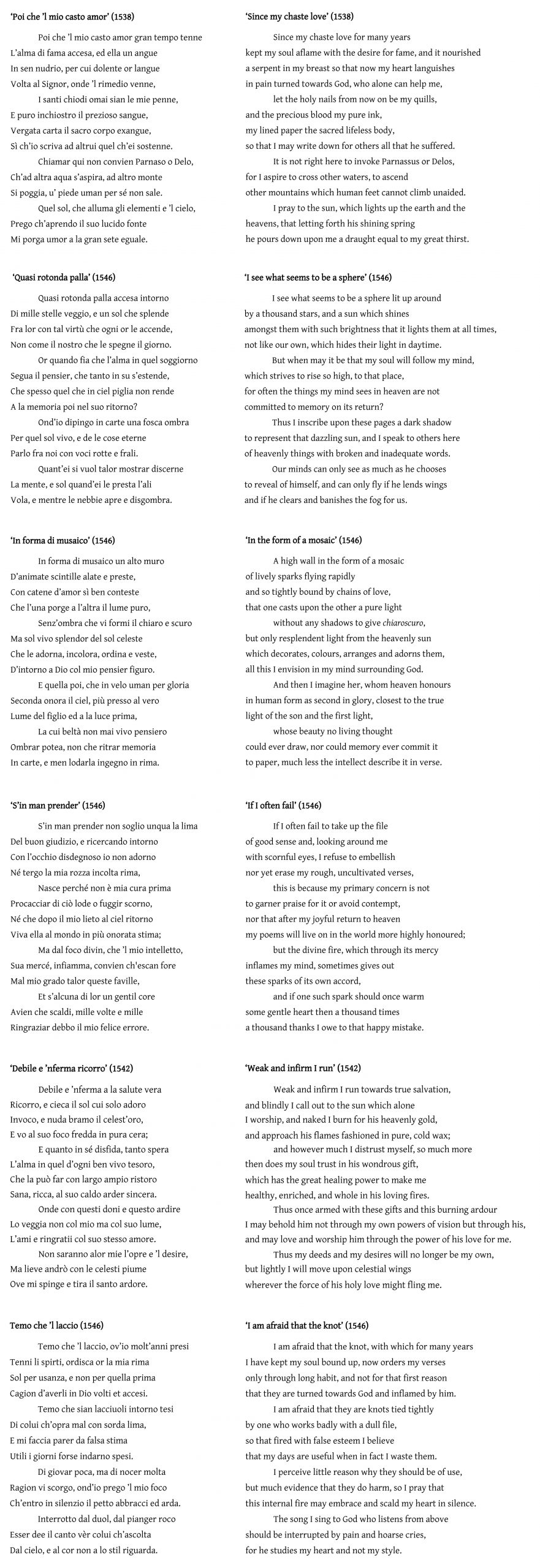

The following poems cast light on the Neoplatonic tone of the friendship between Vittoria Colonna and Michelangelo Buonarroti as well as showcasing some of the key themes and techniques of Colonna’s spiritualised Petrarchism or rime spirituali. They are all included in the manuscript she prepared in around 1540 as a personal gift for Michelangelo. A page of the manuscript with one of the poems here cited is reproduced below.

In Colonna’s verses we see her debt to Petrarch, particularly clear in the poet’s oscillations between opposing states of doubt and certainty, heat and cold, fire and ice: this is undercut by a quiet but notable self-confidence which is entirely her own. Even as the poet expresses doubt about the efficacy of her poetry as spiritual work, she at the same time celebrates her status as God’s instrument and documents her slow and incremental progression nearer to him. She bemoans the inadequacy of her intellect and her pen in the form of beautifully crafted sonnets, and offers them to her friend Michelangelo as a model for his own spiritual attitude.

The poems are discussed and cited in whole or in part in Abigail Brundin’s chapter ‘”A Man within a Woman, or even a God”: Vittoria Colonna and Sixteenth-Century Italian Poetic Culture’ (see FoI, 292-305). The date of first publication of the poems is given in brackets after the title.

For searchable text page – click here

Source

Italian texts and English translations are from Abigail Brundin, ed. and trans. (2005), Vittoria Colonna: Sonnets for Michelangelo (Chicago University Press, 2005).