Abu Tammam

[Abū Tammām Ḥabīb ibn Aws al-Ṭāʾī]

(c. 796/807–850)

The lifetime of Abū Tammām coincided with the zenith of the Abbasid Caliphate whose dominions stretched from North Africa to Central Asia. The period witnessed an unprecedented cultural flowering in which Arabian, Hellenic, Iranian and Indian elements were combined and transformed into a new guise under the banner of Islam. This singular age found in Abū Tammām a poet of genius commensurate with its achievements and ambitions. Descended from a Christian family in Southern Syria, Abū Tammām converted to Islam, adopted an Arab tribal name and rose to become the court poet of choice for high dignitaries of the Abbasid state, including three Abbasid Caliphs. The panegyric mode had existed in Arabic poetry since pre-Islamic times, but Abū Tammām elevated its range and transformed it from a tribal to an imperial medium which was destined to live on in the Persian and Turkish laudatory hymns composed centuries later for Mughal Emperors and Ottoman Sultans.

Abū Tammām aroused controversy as the daring protagonist of a new style of poetic expression which came into being at that time. Termed al-badīꜤ (‘the unprecedented’), it transformed the inherited tropes of poetic convention into multilayered metaphors conveyed in complex diction which reflected the intellectual and philosophical acumen of the age. The difficulty of much of his poetry meant that posterity came to remember Abū Tammām rather more on account of the Ḥamāsa, a popular anthology of early Arabic poetry which he had assembled during a winter spent in Hamadhan, than for his own writings. The twentieth century rediscovered Abū Tammām as one of the greatest Arab poets, and his works have inspired many modern writers.

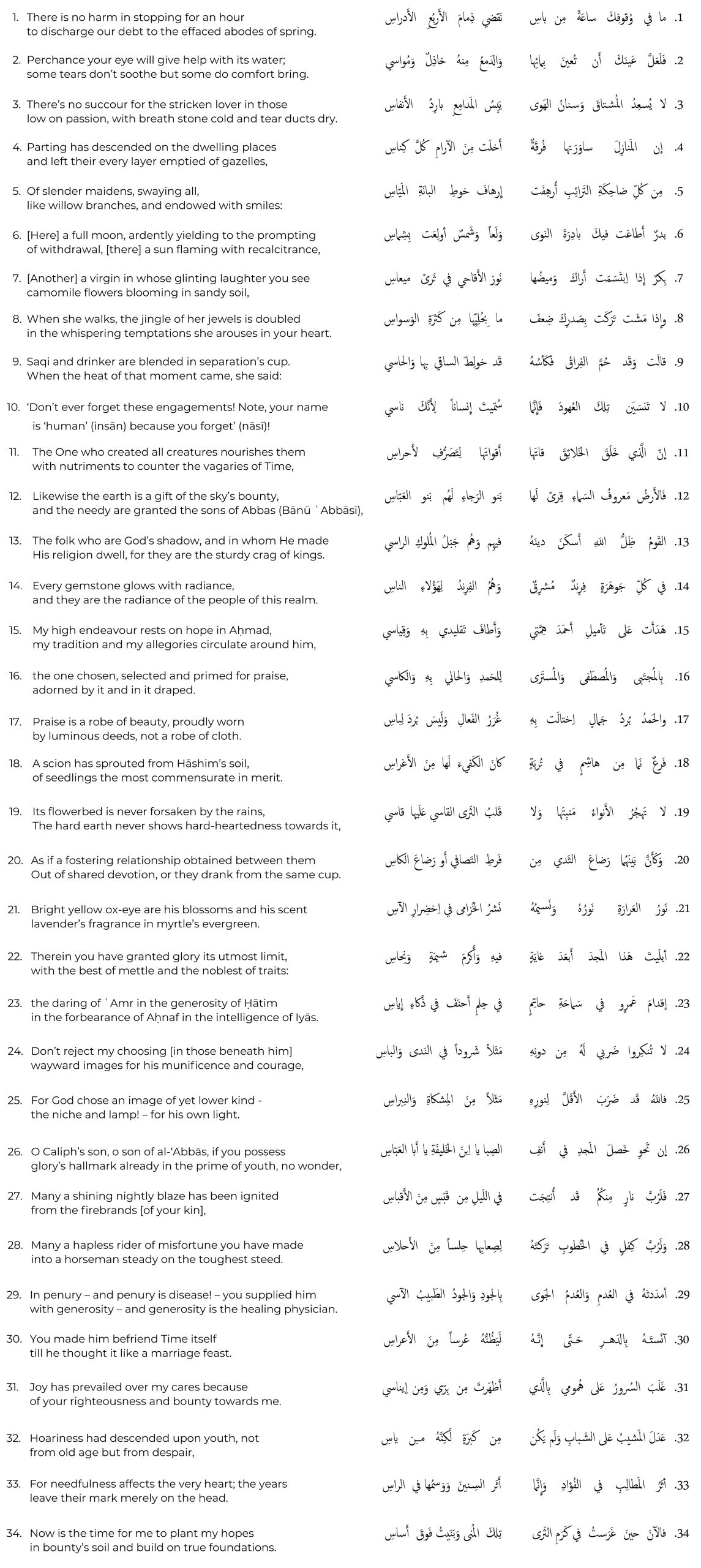

Panegyric for Crown Prince Aḥmad ibn al-MuꜤtaṣim

The poem is cast in the qaṣīda form inherited from pre-Islamic times. Like many an ancient poem, it begins with the poet weeping over the proverbial vestiges of a campsite where he had encountered love in bygone days. The opening section serves to introduce conceptual themes developed in the remainder of the work. Notable among them is the life-giving relationship between irrigation, soil and plant life, which the ensuing section of praise shows to be manifest at a superior, abstract level: in the interaction between God’s bounty as rain, the Abbasid dynasty as fertile soil, and the resulting social order as the fruit of benefit for all. First introduced through the parched soil of the abandoned campsite, the theme concludes the poem metaphorically with the image of the poet planting his hopes in the bountiful earth of Abbasid Kingship. These and other analogies in the poem give expression to a vision of the universe as composed of hierarchically stratified levels which stand in a mirroring relationship to each other. It reflects the Neoplatonic and Neopythagorean cosmology prevalent at the time.

The poem was composed in praise of Aḥmad ibn al-MuꜤtaṣim, the son and designated successor of the reigning Caliph al-MuꜤtaṣim (d. 842). Though not one of Abū Tammām’s most celebrated works, it is of special interest for the purpose of this Anthology because Aḥmad ibn al-MuꜤtaṣim was also the dedicatee of the so-called Theology of Aristotle, an Arabic adaptation of Enneads IV–VI by Plotinus. It had been compiled under the supervision of al-Kindī (d.c. 873), the first major Arabic philosopher, who was one of the mentors of the young prince. Al-Kindī was present when Abū Tammām recited the poem and took exception to one of its verses. For a discussion of the poem, including the altercation between poet and philosopher, see Stefan Sperl, ‘Stages of Ascent: Neoplatonic Affinities in Classical Arabic Poetry’, FoI, 106-13.

Image by Stefan Sperl

For searchable text page – click here

Notes

1. All four are heroic figures of old whose exploits became proverbial. ꜤAmr ibn MaꜤdī Yakrib was a famous knight who converted to Islam and took part in the Arab conquest of Iran where he lost his life. Ḥātim al-Ṭaʾī was a pre-Islamic poet and paragon of generosity. Aḥnaf ibn Qays was an early Muslim general famous for his steadfastness and forbearance. Iyās ibn MuꜤāwiya acquired an enduring reputation for quick-wittedness as chief judge of Basra under the Umayyads.

2. A reference to the famous ‘light verse’ of the Qur‘an (24:35).

Source

Abū Tammām (1969), Dīwān bi-Sharḥ al-Tabrīzī, M. ꜤA. ꜤAzzām (ed.), vol. 2 (Cairo, Dār al-MaꜤārif), 243-252. English translation © Stefan Sperl.